Maxim Magazine

The door creeps open with unusual caution and in walk two girls—clutching purses, teetering on heels, smacking their lips. They timidly work their way through the cluttered tables and chairs, leaving a trail of toppled empties and calling for some guy named Chad*.

Pent-up engine room mechanics lick their chops, catty chorus girls sharpen their claws, and somewhere in the corner Chad—a ship musician new to the scene—senses he has made a very big mistake.

“Never invite animals to Crew Bar,” whispers Evan the Illusionist.

“Animals?” asks Chad.

“Passengers,” says Evan.

Chad jumps up and leads the girls out the door and up the stairwell they never should have seen. But he knows he’s on the surveillance camera with them now, and tomorrow there will be punishment. This is his first contract on a cruise ship, but soon he too will start calling the passengers “animals,” and he will never again fool himself into thinking any of them could ever blend into the world of the crew.

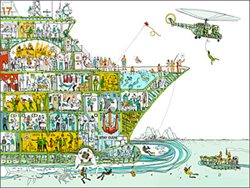

Welcome to the other side of the pleasure cruise, the place where the red carpet and teal wallpaper end and the smiles in uniform either drop to frowns or curl up into sinful grins. It begins behind every door marked crew only, and it’s a world unknown to everyone but those running the ship. That is, until we gained entry—spending seven days on a boat with the people whose cruise never ends.

DAY 1: SHIP TIME 17:00, SUN DECK

It’s embarkation day at the Port of Los Angeles, and the sun deck is packed with passengers sipping the first of many rum specials, oohing and aahing at the first of six Pacific sunsets. We’re setting out for the Mexican Riviera aboard a 92,000-ton marriage of German engineering and Middle American luxury. The 1,120 staterooms are booked to capacity with well over 2,000 passengers. Longer than a football field, it makes the Titanic look like a tugboat.

Each year 12 million Americans file onto cruise ships in port cities such as Miami, L.A., New York, and Seattle, bound for places like the Caribbean, the Mexican Riviera, and Alaska. Some will miss their departure time and have to chase their luggage by boat or plane, at their own expense, until they can catch the ship at the next port of call. Some will be the victims of crimes in the murky jurisdiction of international waters, and some will be the perpetrators. A handful will die on board, and a handful will go missing overboard. A few thousand will get the stomach flu, but the vast majority will get exactly the dream vacation they were looking for; because on average, for about every 2,000 passengers aboard a ship, there are roughly 1,000 crew there to make sure of this.

They are the lifeblood of the nearly $25 billion-a-year North American cruise ship industry—from the dishwasher working 72 hours a week for $400 a month to the magician working two hours a week for $10,000 a month.

DAY 3: SHIP TIME 13:00, PARADISE BAY POOL, DECK 12

Lounging on an upper tier of the sunbathing decks by the pool, Evan the Illusionist is appraising this week’s new batch of women. His tanned and toned physique covers the fact that, at 35, he’s older than most of the other entertainers on board. In a pile on Evan’s chest are the weekly newspaper clippings his father sends to his Port of Los Angeles P.O. box. He says reading these makes him feel like a kid off at summer camp instead of a man without a home.

“I did some TV work last year,” says Evan. “I’ve got an agent in L.A. But then I got offered another ship contract, and I couldn’t afford not to take it.”

Evan is at the top of the crew ladder. He lives in an officers’ cabin, has passenger privileges, and earns top dollar for his two hours of work a week. He spends most of his days by the pool sending drinks to young women across the plastic adult play set of faux palm trees and curly slides. A waiter well familiar with this routine carries over the offerings and points back at Evan. The ladies shoot big smiles, recognizing the shock of wavy black hair from last night’s headline act at the Starz Theater—where Evan the Illusionist pulled a few dozen Ping-Pong balls out of his mouth, turned them into balloons, and then bisected a pretty young dancer with a piece of sheet metal.

Lying on the chaise next to Evan and sharing the magician’s bucket of Coronas is Ray, a 30-year-old pothead surfer turned comedian. Ray criticizes Evan’s game while he thumbs a stripe of sunscreen onto his nose. “Have some balls, man. Just go over there,” chides Ray, brash and confident on the surface, but at the end of the day just a cougar hawk with a good line of talk. Evan, on the other hand, is all chivalry and shyness off-stage, but it’s he and not Ray who’s the center of several ship rumors of backstage threesomes and illicit affairs. As they debate their philosophies of seduction, a poolside cover band from Trinidad plays “Red Red Wine” for the 1,000th time since we set sail.

Both Ray and Evan have used their countless hours at sea to become professionals at the pickup. Whereas their land-based counterparts might spend a couple of nights a week at this pursuit, for these men it’s a full-time job. They come on board thinking they’ll write the next hot screenplay, read the classics, teach themselves to play guitar—all those things a guy with time on his hands will set out to do before he takes women and booze into consideration. So then they end up doing this seven days a week and God knows how many hours a day—forever working on the tan, the buzz, and the perfect approach.

“You do your job and then have 20 hours of free time a day,” says Daniel Thibault, CEO of Proship Entertainment, a Montreal-based cruise ship talent agency. “Some people can use it really well as a stepping stone to another level in their careers. Other people just get lost there, start drinking till oblivion, and do the same routine over and over again, and all of a sudden it’s all they can do.”

Evan throws his ID charge card down for another round of drinks, and Ray leans over the railing to watch a fortysomething woman sunning on her stomach, reach behind her back to undo her bikini top against the threat of tan lines.

“Naughty girl,” whispers Ray.

“In the ’80s, maybe,” says Evan.

“That’s a sexy woman, man. I don’t care how old she is,” says Ray.

“That’s a naughty girl,” says Evan, pointing to a young woman coming down the slide. “She looks over 18, right?”

Ray shrugs. Evan flags down the waiter to send over a drink.

DAY 5: SHIP TIME 20:00, STARZ THEATER, DECK 12

The 1,000-seat theater is packed to capacity for the adults-only ’70s song-and-dance show. The Jamaican cruise director sashays around the stage in a Gucci suit, three buttons of his shirt undone, warming up the crowd with an endless rendition of the ’60s bubblegum-rock hit “Hey! Baby.” Oozing charisma from every pore, he embodies a cruise ship’s rags-to-riches fairy tale of working your way up from the bottom—in his case, from room steward to cruise director. When he’s not wooing widows or talking weather with family men, he’s been known to strut his stuff in the crew bar in a pink crop-top. At the back of the theater, Captain Hans sits in his private loge like Caesar at the Colosseum, his gold epaulets and Papa Hemingway beard glowing in the house lights. On the ship he is the final rule of law; if there is a fight in a bar it’s he who decides who gets locked in the brig. If there’s a disturbance among the crew, Captain Hans decides who should be fired. Whenever anyone in the crew mentions Hans–-men and women alike—they say his name the way a schoolgirl speaks the name of her crush.

Finally darkness falls on about 1,000 gray heads, and a few bars of Queen’s “We Will Rock You” rumble through the room. As the beat reaches a crescendo, the stage lights come up to reveal 20 fit and attractive young singers and dancers holding sultry poses in fog-machine mist. Their mesh and leopard-print attire borders on indecent. Housewives squeal as male dancers taunt them with sweaty biceps and roving hands—fooling every one of them into thinking it’s women who interest them and not the other male dancers in their troupe.

The girl-next-door lead singer has a penchant for threesomes, and left a job playing a main character at Euro Disney to work on the ship. Her handsome male counterpart ran away from Off-Broadway obscurity to be a star at sea; on port days he can be found sprawled out by the pools of portside resorts wearing nothing but nipple rings and a Burberry Speedo. The background dancer, 25, has been on ships since she was 19 and doesn’t have much of a life back home anymore. Because, explains cruise ship entertainment director Thibault, “If you stay on ships too long, no one back on land remembers you.”

SHIP TIME 23:00, CALYPSO BAR, DECK 12

The show’s performers are now sipping appletinis at Manhattan’s Martini Bar—an alcove off the Calypso Bar that looks like a three-walled sample room at Ikea. They’re staying off the serious drinking for now, because tomorrow is Acapulco Night, the port where they’re all allowed enough shore leave for things to get messy.

Before long it’s curfew hour for the performers. They’re dressed like passengers—if a bit more stylish—but they still have to wear their name tags in passenger areas, and at midnight they find their way to the crew only doors that lead them down to the bowels of the ship. The curfew is just a taste of the big brother presence of authority felt among the crew. The ubiquitous surveillance cameras serve as an around-the-clock warning to would-be rule breakers. Crew infractions aboard this ship range from the comical to the criminal. In a Deck 2 laundry room, a group of female dancers left six dryers filled with their clothes and returned 45 minutes later to find that their underwear had been stolen.

News travels fast on a ship, and the dancers quickly discovered that a group of men had auctioned them off within the crew. The men were all fired. In another incident, security was called to the lower decks when eight men were caught cooking a whole pig’s head in their cabin on a hot plate—here again, all were fired. An entire shift of engineers was reprimanded after treating a particularly surly superior to a week without plumbing or air-conditioning in his stateroom. But then there are the darker stories: a singer who was roofied by a juggler, a dancer who was twice sexually assaulted by other crew members. Many of the crew are paid in cash, which leaves them particularly vulnerable to theft.

The issue with crimes at sea isn’t that people are at greater risk on a ship than they are on land; the on-board crime rate is lower than most national averages, and the crew’s rules are strict and punishments harsh and final. The problem is that once a crime is committed, a conflict of interest arises. “The cruise lines don’t want their passengers or their crew members to be crime victims,” says Charles Lipcon, author of Unsafe on the High Seas and perhaps the world’s most successful prosecutor of cruise lines. “But if it happens, they become the adversary of the victims; they work against them because they’re afraid they’ll have a financial liability.” Added to that threat is bad press if someone is convicted of a crime aboard one of their ships.

In recent years a series of high-profile disappearances, unprosecuted rapes, and other unsolved mysteries at sea has brought increased scrutiny to the cruise industry. The FBI opened 184 cases of crimes on cruise ships between October 2001 and February 2007, including 101 sexual assaults, 12 missing persons, and 13 deaths. According to another source, 131 people have gone missing or overboard since 1995. “The FBI numbers are low,” says Lipcon. “The cruise lines only have to report crimes involving Americans to the FBI, and even those are underreported.”

Most of the time the high-tech eye of authority and the threat of strict punishment keep the tension of life at sea in check. But the tension is always there, and it’s easy to see when the booze starts flowing down in the Crew Bar. On this ship there is a .08 blood alcohol limit for the crew at all times, and though it isn’t all that uncommon for people to be fired for intoxication, the rule seems to go entirely ignored on Acapulco Night.

DAY 6: SHIP TIME 23:00, CREW BAR, ACAPULCO NIGHT

The Crew Bar peace has been shattered by the 12-hour furlough in Acapulco, where even the lowest echelons of the staff are allowed a few hours of shore leave to squander their meager incomes at beach clubs with bungee-jumping cranes, cage-dancing sorority girls, and bare-bellied Mexican barmaids hawking shots of cheap tequila. The scrum at the bar are waving their charge cards, while six-packs of Amstel Light and Smirnoff Ice are floated overhead like crowd surfers in a mosh pit. The floor is sticky, and the air is choked with smoke, the smell of sweat, and the aggression of drunken men who’ve gone too long without touching a woman. “You have these people working all the time, cooped up. They don’t have a chance to have a relationship and they get drunk and this is what happens,” says Lipcon.

A scene erupts by the door as a Caribbean woman slams her boyfriend against a wall. “’Dis happen ev’ry Acapulco Night!” she yells, in a frenzied patois. “Why you do this to me?” she screams before letting go of him and stomping back to the dance floor to join the sweaty mob that spawned the drama in the first place.

In the gay corner, Pacific Islanders who are “gay at sea” but have families back home stare down a ballroom dancer and a “would’ve been, could’ve been” Broadway singer. On a vinyl banquette, a Bavarian receptionist bawls into the arms of a man who wants to sleep with her. One by one slender chorus girls succumb to a day of hot sun and a night of hard drinking and are escorted away from the wolfish stares of the dishwashers and mechanics by uninterested male dance partners—back to their tiny cabins to throw up, pass out, or both.

The night has begun to topple over toward dawn and the threat of work in the morning. Soon the hallways outside will fill with crew members stumbling back to cramped bunks below the water line—six to a cabin without a bathroom—and dancers headed to the semi-privacy of their one-roommate abodes. Officers and headline acts will retire to private cabins, and a mixture of them all will wander around knocking on familiar doors for one last shot at some action.

Upstairs the all-night buffet is operating as usual, dishing out soft-serve ice cream, fish ’n’ chips, and pizza to a graveyard shift of elderly travel-point collectors, middle-aged Parrotheads, and their hyperactive, sunburned children. The Calypso Bar’s dance floor is hopping with stiff-backed men sweating through their Tommy Bahama shirts and divorcées with rum-blushed cheeks singing along to Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer.” They’re a happy lot. They’ve shared hot tubs with strangers, gotten drunk at breakfast, and eaten three lunches in one day. This is their ship for the week, and the staff has helped them believe that their week is the best that’s ever been and that everyone working on the ship is thrilled to be here to enjoy it with them.

Soon they will all be asleep in their staterooms, dreaming of the morning maid service, the breakfast buffet, and a tour of some town whose name they can’t pronounce from the safety of an air-conditioned van. None will sense the downstairs madness or that tonight’s sick and stumbling dancers are tomorrow’s headline entertainment.

They don’t need to know about the lives of the crew any more than they need to know that on last week’s cruise, this ship struck and killed a sleeping gray whale and had to divert to Mazatlan, Mexico so the propeller pods could be unclogged and the blades replaced. They don’t need to know the rumors among staff that when one of them dies, the body is stored in a walk-in freezer. They don’t need to know that the food they leave on their plates is fed to the fish—down to

the chocolate, the salad greens, and the curly fries. They don’t need to know that when they flush their toilets, the remains of their Promenade Grille hamburgers and their surf ’n’ turf dinners at Bogart’s Steakhouse are trapped in a tank, where they are solidified and stored for months.

They don’t need to know any of these things, and they never will, just as long as they don’t stay here long enough to notice that all is not as it seems.